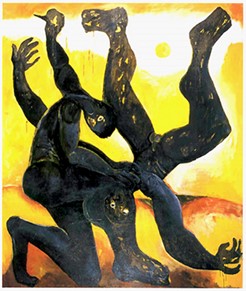

Da Rosa creates human figures. They can be statuesque, but more usually they are twisted and contorted. They can indulge in athletics, dance or struggle. Some of them are isolated and in anguish, but just as often they are joyful or in ecstasy. Only rarely do we get the feeling of relation and a studio situation which we find so frequently in Matisse. Most striking is the fresh and unexpected relation of silhouette to rectangle and a confrontational, directness of address. Always there is the idea of universal man, naked but without any special sexual emphasis. Always there is titanic passion and energy. Like Picasso, da Rosa is a sculptor/draughtsman par excellence. His color and textures can be daring and aggressive, but the picture is ultimately carried by a draughtsmanly idea. And it is natural enough that da Rosa sometimes turns to figure sculpture or combines sculpture with his painting. His is adept in both mediums and his sculptures are no less passionate and monumental than his painting. It should be noted though, that his figures have their own distinct proportions with massive legs and hips and a diminished upper body.

The human figure, in the context of postwar painterly abstraction, first appeared in the work of Jackson Pollock. These were large, sketchy figures which were more the product of gesture than nature. Pollock’s example was soon followed by Willem de Kooning, Robert Goodnough and others. But these developments were submerged in the 60’s by Color Field Painting and Minimalism, both of which were purely abstract. Only in the late 70’s, with figures like Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, George Baselitz and the Italians, Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi and Mimmo Paladino did painterly figuration again gain center stage, now under the title of “Neo-Expressionism.” Yet despite occasional successes, this tendency did not produce a major figure, a single painter who can match Pollock. A member of the New New group of painters, Lucy Baker did a brilliant series of the gestural, figurative works in the middle 80’s, but these remained an isolated phenomena, a lone fulfillment of New-Expression’s potential. With his work of the early 90’s, da Rosa’ took his place beside her. What is more, neo-figuration is far more central to da Rosa’s art than it is to Bakers.

Da Rosa was born in the town of Ponte do Sor in Alextejo, Portugal, that province which has been the birth place of so many artists and writers. His father, the owner of a small factory, was a highly cultured man who instilled in him the love of the arts. As a young man da Rosa moved to Lisbon and quickly fell in with a group of artists and writers. First drawn to literature and the theater, he published a book of poetry at age 18. Soon thereafter, he attended the Society Belas Artes where he began his study of painting. But the year was 1958 and Portugal was under the dictatorship of Salazar. Da Rosa found the atmosphere of the Society hyper conservative and stultifying. He soon left and in 1960 he was able to visit Paris for four months. Now committed to painting and the visual arts, his idol was Picasso even though his temperament led him more to German Expressionism especially the Blaue Reiter group and the work of Franz Marc.

Unable to secure a living in Paris, da Rosa moved to Germany, settling in Dusseldorf for several years. Here it was that he met Isable Oliveira, who was to become his life’s companion and champion. Da Rosa likes to travel and visited many places in Europe at this time. Also he applied to enter Canada as a resident and, in 1962, after first moving to Brazil, he was accepted for admission in Canada.

He first went to Montreal, but soon moved on to Toronto. Here he briefly attended the Three Schools of Art and had his first one-man exhibition in 1966 at a bookstore gallery. After that he was represented by Roza Mezei of the R.M. Gallery for several years. He continued to travel extensively visiting California, New York, and other places in the United States and Canada. In 1969-70 he spent a year in Mexico, first in San Miguel de Allende and then in Mexico City. It was during his stay in Mexico City that da Rosa had a “breakthrough” experience, as he puts it, watching David Siqueiros working on the huge mural “The March of Humankind” “Towards the Cosmos”. Da Rosa had been drawn to the human being as his subject matter ever since he began to paint, but Siqueiro’s work challenged him by its grand ambition and prompted him to focus on the figure more exclusively.

Da Rosa was admitted for residence in the United States in 1987 as an “Artist of Merit” and he went to live in Miami. This is where his art finally came to fruition. Until now he had shown talent and promise, but his work remained all too polite and familiar. Between 1988-1991 his pictures became larger and underwent an eruptive development with the series “American Dream”, 1989, “Urban Realities”, 1990; and a huge 15.5×28 ft. magnum opus, “Joseph Beuys Sweeps Up Berlin”, 1991, which showed over life size figures both in painted relief and three dimensions climbing over and gestulating before a wall. The latter work extends some nine feet into the views space. (Da Rosa later removed the pieces in the round because he found that the painting and relief were more effective by themselves).

In 1991 he began to realize his figures with heavy applications of white acrylic paste instead of the vivid flesh tones he previously favored. This made the figures seem skeletal and more abstract. They now loomed larger and da Rosa began to distort them more boldly. His most recent pictures are da Rosa’s most mature and personal works so far. He has said that the large chromatic skies of South Florida have influenced both his scale and his color. It may seem contradictory that Miami has provided the environment for the flowering of such a raw northern expressionist vision. But in this, da Rosa is more the rule than the exception. Expressionism characterizes many of South Florida’s leading figures: da Rosa, Carlos Alfonso, Arturo Rodriquez, José Bedia and Norman Liebman. They seem to be reacting against the sunny idyllicism of the area. In any event, da Rosa is one of the most exciting artists working anywhere today. He applies the European cultural tradition with a contemporary urgency. He offers pathos without sentimentality. His is a fully modern humanism with an eternal appeal.